Six feminist alternatives to Jane Austen for a Bank of England note

The choice of the author to represent women on the £10 note is a safe and bland option, compared to Boudicca or Mary Seacole

-

![Belinda Webb]()

-

- guardian.co.uk, Thursday 25 July 2013 16.57 BST

- Jump to comments (387)

Jane Austen as a choice of woman to be on the £10 bank note would be fine, if we were in the 18th century. I can’t help but feel she is the safe, bland, acceptable, middle-class choice. Austen is the woman men don’t mind giving us as a representation because she is no threat to the prevailing order whatsoever.

Women do anger. Yes, I know, not that surprising to us, but something that is hardly acknowledged in public life. I’m not talking “passive aggressive drawing-room polite snide à la Austen”, but rage and revenge. Here is my list of women fit to represent this:

1. Boudicca (AD 60/61)

The Angry Woman; Queen of the Iceni. When Boudicca herself was beaten, and her sisters and other Iceni women were raped and beaten by the Romans, this woman did not stay home and cower. She got on her horse and led an army of fighters to get their own back.

2. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)

She wrote, among other things, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792): a highly intelligent, yet clear and sustained, argument for why women needed equal educational opportunities. She didn’t just take on any old Tom, Dick, or Harry in arguing this – but the beloved Edmund Burke. She also gave us Frankenstein. OK, the creator of Frankenstein – Mary Shelley Wollstonecraft.

3. Mary Seacole (1805-1881)

The woman Michael Gove wanted to shove off our national syllabus. The Jamaican nurse, of Scottish and Creole descent, who risked her own life and health in going to the Crimean battleground to care for the injured, was voted the greatest black Briton in 2004.

4. Marie Stopes (1880-1958)

Born of a feminist mother, who was the first woman in Scotland to get a university certificate (she should have got a degree but they refused – degrees were only for men), Stopes represents the coupling of academic rigour and political engagement in order to emancipate women from slavery and empower them with autonomy over their reproductive organs. What’s less well known is that Stopes also played a key role in an attempt to stop education authorities from sacking women teachers.

5. Aphra Behn (1640-1689)

The first woman to earn her living by her pen. And, it could be argued, beat Daniel Defoe by about 30 years as creator of the modern novel, by writing Oroonoko, a poignant anti-slavery novel. And she was also a valuable spy for the English court.

6. Emily or Charlotte Brontë (mid-1800s)

I’ve always believed that there are two types of woman – those who root for Austen, and those who prefer their fiction wild, angry and passionate, as written by the Brontës.

Do you agree with Jane Austen as the choice of our token woman, or do you feel it’s too safe – as safe and bland a choice as women are likely to ever be given? Who would you choose, and why?

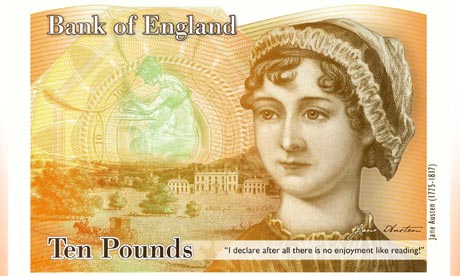

Why that Jane Austen quotation on the new £10 note is a major blunder

Duplicated many million times on the new £10 banknote will be a line in praise of reading – it’s a shame it was uttered by an Austen character who had no genuine interest in reading at all

Has the Bank of England governor actually read Pride and Prejudice? As Mark Carney posed in front of an enlarged mock-up of the design for the new £10 note, he spoke of Austen’s greatness and indicated that there would be due attention to diversity in the choice of future bank-note characters. It was a small PR triumph for the new man at the top.

Yet surely there has been a blunder. The new note displays an image of Austen based on the only certain surviving portrait of her, a drawing by her sister Cassandra. Fine. It also blazons forth some of the great writer’s immortal words. You can imagine being the Bank of England employee given the task of finding the telling Austen quotation. Something about reading, perhaps? A quick text search in Pride and Prejudice turns up just the thing: “I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading!”

The trouble is that these words are spoken by one of Austen’s most deceitful characters, a woman who has no interest in books at all: Caroline Bingley. She is sidling up to Mr Darcy, whom she would like to hook as a husband, and pretending that she shares his interests. He is reading a book, so she sits next to him and pretends to read one too. She is, Austen writes, “as much engaged in watching Mr Darcy’s progress through his book, as in reading her own” and “perpetually either making some inquiry, or looking at his page”. He will not be distracted, so “exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his”, she gives a great yawn and says the words that will appear on the bank note.

She is interested in books in one way. She and her brother are nouveaux riches, who have inherited their wealth from a father who was “in trade”. Now they have a big rented house – but no books to put in it. You can display your status with an impressive library (Mr Darcy has one), so she is keen that her brother procure some volumes as soon as possible. “When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library.” But she won’t be reading any of its contents.

Duplicated many million times on the banknote will be a line in praise of reading that, comically, could only be used by someone who didn’t mean a word of it. Time for a campaign to use a different quotation?

Business

Books

Life and style

World news

More from Shortcuts on

Business

Books

Life and style

World news

-

More on this story

-

![Matt Kenyon austen]()

The Jane Austen banknote victory shows young women are packing a punch

Zoe Williams: The fight with the Bank of England is just one example of how determined and lethal the new generation of feminists is. Mervyn Kings everywhere watch out